Any history of racial politics of the Victorian era is alive with booby traps for reckless pundits. Were colonists hardy survivors or plain bigots? The historical record is riddled with trigger wires. Researchers are left with fragments of paper. No eyewitness is available for questioning.

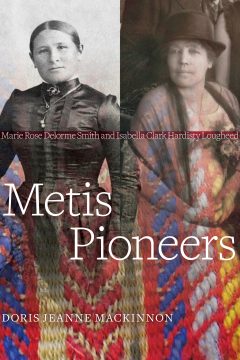

Dr. Doris Jeanne MacKinnon, a Red Deer historian, takes the field with Metis Pioneers, a thoughtful account of interracial politics in an era where serious people ascribed characteristics to blood lines for humans and cattle alike. Society manufactured a descending scale of racial superiority. Indigenous women were always at the bottom.

Metis Pioneers chronicles compelling biographies of Victorian women on the Prairies. The reader is guided pleasantly along by MacKinnon’s meticulous research – until. Time freezes on page 125. The gentle lead-up makes it all the more arresting. MacKinnon is a scholar, not a headline writer for the Police Gazette.

Peter Lougheed’s grandmother was Métis. The late Alberta premier rarely spoke of the fact, but too much can be made of this omission. Lougheed never mentioned his alcoholic father, either. He was a man of the pre-Clinton era when politicians considered it cloying and pathetic to weep softly in public and mutter I-feel-your-pain.

MacKinnon’s research suggests Lougheed did not really know his grandmother, Isabella Clark Hardisty Lougheed. He was 8 when she died in 1936. Lougheed recalled her as a remote figure who lived in a mansion and once made a cutting remark that Peter had the same name as the family dog.

Isabella was undeniably Métis. “Her racial features confirmed her ancestry,” write the author. She neither denied nor celebrated her roots, instead cultivating “the persona of the gracious woman.” Historian MacKinnon describes her as a member of the fur trade aristocracy, the niece of one senator, wife of another, grandmother to a premier. Isabella Lougheed attended private schools, traveled by chauffeured limousine and lived in a sandstone mansion that still stands in Calgary, the Beaulieu National Historic Site.

The Prairies then and now was an egalitarian society. It was no scandal to marry for love. Isabella was simultaneously a Daughter of the Empire and a member of the Alberta Pioneer Association where they enjoyed moose steak and the Red River Jig.

Yet racial divisions were unmistakable. Métis had no legal standing. First Nations could not even vote. Author MacKinnon notes Grandmother Lougheed left no diary. Her deepest thoughts are unknown. Was she brave or conflicted, victim or champion, feminist or poseur?

Then, the jaw-dropping moment on page 125. MacKinnon uncovers a rare interview Isabella gave a Toronto newspaper reporter in a feature on prominent ladies of the West. “In Calgary’s early days it was almost impossible to get help,” said Lougheed. “The squaws and half-breed women were all that were available. They could wash but not iron, and they were never dependable.”

Here Lady Lougheed becomes a Métis heroine to break your heart. Her remark was gratuitously stupid, yet perhaps judgment is too harsh. Isabella was not the one to starve First Nations or mandate the celebration of Empire. It doesn’t fall to everyone to be Nelson Mandela.

“The interview provides a rare example, in Isabella’s own words, of her own management of her public image,” writes MacKinnon; “This is the one and only time we know for certain she had Indigenous women in her grand home in Calgary, and she took the opportunity to let her new community know what she thought of ‘squaws’ and ‘half breeds’.”

Metis Pioneers is a compelling journey through the Victorian minefield of race and politics. It works.

By Holly Doan

Metis Pioneers: Marie Rose Delorme Smith and Isabella Clark Hardisty Lougheed, by Doris Jeanne MacKinnon; University of Alberta Press; 584 pages; ISBN 9781-77212-2718; $45