Ask oldtimers what pre-industrial life was like in Yukon and Northwest Territories and they recall the sound of sled dogs galloping through the snow, the blue gleam of moonlight in winter and smell of fresh caribou steaks drying on spruce boughs.

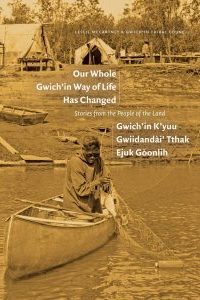

Anthropologist Leslie McCartney asked twenty-three Gwich’in elders as old as 99. Their stories are chronicled in Our Whole Gwich’in Way Of Life Has Changed, a big, beautiful volume, 848 pages. It is warm and human.

There is a blank space in all history books dotted here and there with guesswork and anecdotes. Missing are accounts of daily working lives prior to the 18th century. There are no written descriptions by workaday Norwegian sailors or Hessian miners or Mongolian herders since ordinary people had no means of writing it down.

It took mammoth investments in public education and inexpensive pulp paper before people kept diaries and family scrapbooks. They relied instead on storytelling, what researchers call oral history. So did the Gwich’in. “Oral history stories are not so much about getting the facts correct as they are about ways of talking about the past and hearing voices that would have been, to date, marginalized,” write authors.

Readers learn adoption of orphaned children was commonplace, as were arranged marriages. The Gwich’in believed in prophecy, prized self-reliance and thrived on an all-meat diet.

“Meat was what we lived on most,” one elder recalled: rabbit and boiled porcupine, whitefish and blueberries in season, but mainly caribou. Annie Benoit, 88, remembers her family followed the caribou herds. “Lots of good places to stay in the bush,” said Benoit. “When they hear about lots of caribou, they move to the mountains and after that they work hard on their meat, caribou meat.”

Children from the youngest age were taught to find food. “Every day they repeated the same thing to us, teaching us our survival skills,” said Joan Nazon, 87. “They told us and taught us every day. They always said, ‘We don’t tell you this for now but for your future, so you will be self-sufficient.’”

“No one is going to live like they live today in the future,” said Nazon. “There is going to be starvation. People are going to suffer and there will not be enough food.”

Our Whole Gwich’in Way Of Life Has Changed is a memorial assembled by the Gwich’in Tribal Council. “Most of the elders interviewed are members of the last generation to fluently speak Dinjii Zhu’ Ginjik, the Gwich’in language, as their mother tongue,” the authors write.

“Language determines how we perceive, understand and communicate our world views and deep beliefs. Language is not simply communication; it also serves as a link, connecting people with their past.”

If working lives of Gwich’in people were hard, elders mainly recall those years with fondness. Alfred Semple, 70, looked south to the cities and saw no obvious signs of superiority. “There are many, many people down south,” he said. “Many are poor and homeless and do not have much to eat.”

“Today they just work for money,” he said. “Money, that’s all that is in their head. We never grew up that way.”

By Holly Doan

Our Whole Gwich’in Way of Life Has Changed: Stories from People of the Land, by Leslie McCartney & Gwich’in Tribal Council; University of Alberta Press; 848 pages; ISBN 9781-77212-4828; $99