Why do civilized governments reach for the bottom shelf on tolerance? Canadians this week put an end to the Niqab Election in which a prime minister literally made a federal case over how somebody’s mother dressed at a citizenship ceremony. That came after cabinet June 18 passed the most embarrassing legislation introduced in a postwar Canadian Parliament, Bill S-7 The Zero Tolerance For Barbaric Cultural Practices Act.

Bill S-7 banned honour killings, forced marriage of 12-year olds and polygamy – practices already outlawed in Canada since at least 1890. The bill amounted to gratuitous needling of Muslims. “We are at a historical watershed,” said then-Immigration Minister Chris Alexander; “If we were to open the door to inaction or paralysis, we would look much like the Afghan government”; “Our policy will remain to ensure that citizenship ceremonies take place among people who have removed their face coverings. That is one of the practices in this country that protects women, protects girls, and protects Canadian values and traditions.”

There is no evidence Stephen Harper or Chris Alexander are personally intolerant of Muslims. They merely found expediency in uttering words intolerant people use. So Professor Ira Robinson cites this chilling 1971 speech by René Lévesque, no anti-Semite per se: “I know that eighty to ninety percent of the Jews of Québec are nervous about the effects of separatism. I know that history shows that a rise of nationalism means Jews get it in the neck. But what can I do about it? I can’t change your history. But I also know that anti-Semitism is not a significant French-Canadian characteristic. The more serious problem for the Jews is that Jews in Québec are closely related to the English community. If they choose to put in with them, what can I do?”

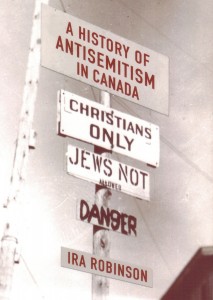

Robinson’s History Of Antisemitism In Canada is timely and intriguing. Robinson is chair of Canadian Jewish Studies at Concordia University; his exhaustive research is historical, and specific to his theme, and makes no mention of niqabs. Yet parallels to contemporary events are striking.

Jews from colonial days were seen as enterprising but suspicious. When Ezekial Hart became the first Jew elected to the Lower Canada legislature in 1807, commentators explained: “The Jews are everywhere a people apart from the body of the nation in which they live”; “A Jew never joins any other nation. He makes it a religious duty, a consistent rule of conduct, to keep separate from other people.” Hart was barred from taking his seat in the assembly.

A History Of Antisemitism details intolerance that is still shocking to readers. Upper Canada banned Jews from holding land titles till 1803, though there were then fewer than 100 Jews in what is now Ontario. The provincial Appeal Court as late as 1949 upheld land covenants forbidding the sale of land to Jews; the chief justice called it an “innocent and modest effort” to establish a “class who will get along well together.” No Jew served in a federal cabinet till 1969, long after France or Germany or the Confederate States of America.

Professor Robinson’s work recounts a success story. “Antisemitism is objectively in decline in Canada,” Robinson notes; Stephen Harper’s cabinet was “the most supportive of Israel in the Western world.” After 200 years, he can wish for his grandson: “May you grow up to see a world in which the phenomenon described in this book is only of historical interest.”

In the aftermath of the Niqab Election, we might wish the same for all Canadians.

By Holly Doan

A History of Antisemitism in Canada, by Ira Robinson; Wilfrid Laurier University Press; 300 pages; ISBN 9781-7711-21668; $29.24