When Powell River, B.C. marked its centennial in 2010 Powell River Living magazine in a special issue enthusiastically recalled the mill town’s first hotel, built in 1911, the first vaudeville theatre (1913), the first dial telephones (1921). There was culture, too, the founding of the annual music fest International Choral Kathaumixw. That’s Welsh, not Indian.

Elsie Paul read the articles in Powell River Living. Her great-uncle was last hereditary chief of the Sliammon people who thrived in the region for millennia. Paul did not enjoy the articles about vaudeville and dial phones. “They’re celebrating this and celebrating that, and how Powell River originated,” she said. “I’m thinking, we were here!”

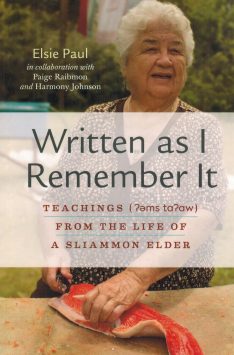

Written As I Remember It is warm and honest, partly a memoir, part ethnography, part Farmer’s Almanac. It draws on a Sliammon Elder’s oral history of a skilled and prosperous people who lived and died here long before they built a company town and named it for an English surgeon.

There are teachings on grief and marriage, tips on how to dry salmon or cure a colicky baby and legends of the people like the story of the telepathic twins. Two brothers were separated as one traveled to nearby Texada Island to camp and fish and his worried mother asked one twin to check on the other: “I’ll meditate on it.’ And he did.”

Emerging later from a trance, he told his mother: “Oh, I found him. He’s OK.” The second brother on returning home explained he was camping on the island when he saw lightning approach, striking three times, each time coming closer. “So he said to his travelling companion, ‘That was my brother. He’s looking for me. Now he’s gone. He’s found us.’”

Written As I Remember It is drawn from 36 hours of recordings with Elsie Paul transcribed, translated and compiled by granddaughter Harmony Johnson and Dr. Paige Raibmon of the Department of History at the University of British Columbia. Here Paul recalls conversations with her grandparents in a narrative that spans more than a century of coastal life.

There was no Christmas or birthdays. “For us as First Nations people I think every day was pretty much the same. It’s the seasons that our people honoured and acknowledged.”

Marriages were arranged. Dowries were paid typically in property like canoes. Children were frightened by the legend of the wild man of the woods who gathered up small boys and girls that foolishly wandered from camp, trapped them in a basket made of writhing snakes and then roasted them for supper: “That was real frightening. I don’t know if that would be acceptable today to scare your children like that, but it worked!”

There were no elections, no politics, no police. Justice was restorative and not adversarial: “In the old system your people dealt with those matters. You had to sit with a family you offended. You had to sit in a circle, and you apologized, and you each had something to say. Say you’re sorry. You admit to what you’ve done. And the people that you victimized have a right to say whatever they have to say. And you resolve that by forgiveness, shaking hands and making amends. And all that style is gone.”

And there was the food, a selection that would cost $120 in a Bay Street restaurant: fresh herring and venison, duck stew, wild blackberries, smoked clams and the famous salmon. “When the fish came here, they would honour the salmon.”

“The oldtimers would go down the beach and welcome, raise their hands to the sea. ‘Come,’ you know, ‘You’ve come back!’”

Written As I Remember It captures a vanished world that survived for 10,000 years and was just as worthy as mill towns with telephones.

Written As I Remember It: Teachings from the Life of a Sliammon Elder by Elsie Paul, with Paige Raibmon & Harmony Johnson; UBC Press; 488 pages; ISBN #9780-7748-27119; $39.95